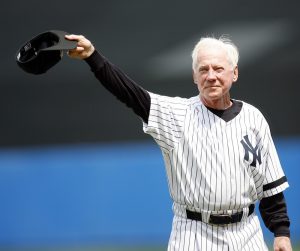

The Little Lefty Who Could – Whitey Ford: 1928 – 2020

And now, The Chairman is gone, too.

In a horrible deadly year which continues to worsen, news of the passing of the greatest pitcher in New York Yankees history struck another blow to the hearts of all Yankees fans, all baseball fans, and indeed, all New Yorkers, as this was one great ballplayer who was a true New Yorker from Day One.

Whitey Ford, Manhattan-born and Astoria-grown, passed away on the evening of October 9, comforted by family and his wife of 69 years, Joan – also of Astoria – while watching his beloved Yankees win the second game of their Division Series against the Tampa Bay Rays, which gave just a pinch of solace to this sorrowful news.

“While there is comfort knowing Whitey was surrounded by his family at the time of his passing while watching his favorite team compete,” said Yankees general partner Hal Steinbrenner in a team press release, “this is a tremendous loss to the Yankees and the baseball community. We have lost our ‘Chairman of the Board,’ and extend our deepest condolences to the entire Ford family.”

Chairman of the Board. That nickname, which was bestowed upon the lefthanded hurler who won more games than other pitcher in Yankees history, 236, by one of his illustrious catchers, Elston Howard, says it all. You can’t get much higher than that in any organization. Chairman. The buck stops there.

The New York area had been blessed by two legends who were christened “Chairman of the Board” in their professions – that skinny kid from Hoboken with the golden voice, Francis Albert Sinatra, and a diminutive southpaw who first played baseball in the streets of Astoria and a sandlot team known as the 34th Avenue Boys, Edward Charles Ford.

Today’s game is used to seeing monstrous pitchers growing taller and taller seemingly every year, 6’5”, 6’7”, and so on – heck, Tampa’s Tyler Glasnow, who took on the Yankees in the ALDS, is 6’8” – not to mention the likes of Hall of Famer Randy Johnson, who is 6’10”!

But here was this New York-tough lefty at 5’10”, and a mere 178 lbs., who pitched for 16 years (it would have been 18, but Uncle Sam gave him an Army uniform for two of his prime pitching years in 1951 and ’52 during the Korean War) and ended with baseball’s best winning percentage in the 20th Century (236-106, .690,) in 498 games, 438 starts, and other eye-popping stats including: 2.75 ERA, 156 complete games, 45 shutouts, 1.215 WHIP, 11 saves

– believe it or not – two ERA titles, 3x AL wins titles, 10 All-Star Games, six World Series titles (again, it would have been 8 or 9 rings, but we’ll get to those in a moment or two) a World Series MVP trophy, and one Cy Young.

And we haven’t even started bragging about his postseason accomplishments. Record-setting! Untouchable all-time records!

Will any other pitcher ever get to match Ford’s 22 World Series starts? No. How about his record Fall Classic 10 wins, strikeouts (94), innings (146), and 33 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings? Not likely.

Ford, who was 91 at his passing, about two weeks short of his 92nd birthday, is the G.O.A.T. of Yankees pitchers. No doubt about it. Certainly Ron Guidry had his moments (170-91, 3.29), and Andy Pettitte actually won more overall (256-156, 3.85), but was maybe one season shy of Ford’s Yankee numbers (219-127, 3.94). Three of Pettitte’s years were spent in Houston – 2004-06.

And it all started just a bridge toll away from Yankee Stadium in Astoria.

Ford was supposed to attend a Queens high school near home, William Cullen Bryant, on 31st Ave., but a boyhood friend, and also a former member of the 34th Avenue Boys sandlotters, Aniello Giovanni, was attending Aviation High School in Manhattan, and they had a baseball team when Bryant did not, so Ford made the commute.

He was a first baseman then, believe it or not, and not a bad hitter at the time, but after a scout suggested he try pitching, he doubled up.

Yankees scout Paul Krichell signed him for $7,000 in 1946, and it was in the minors where Eddie Ford was re-christened with the Whitey designation, thanks to his pitching coach/manager, former Yankee, and future Hall of Famer, Lefty Gomez. You couldn’t help but be dazzled by his bright blond hair, so “Whitey” it became. The nickname didn’t catch on right away, but winners garner monickers of distinction, so when it stuck, it was forever.

Ford was called up to the big club in June of 1950 as a 21-year-old, and was an instant success, winning nine out of ten decisions in 20 games, 12 starts (2.81 ERA), seven complete games.

Can you imagine had he not spent the next two years slugging it out in Army khakis? Ford went 18-6 (3.00) and 16-8 (2.82) in ’53 and ’54 (both World Series wins for the Bronx Bombers), so there were two more rings and arguably another 35 or more wins for his lifetime total, but he never questioned his devotion to honor and duty.

Another reason Ford’s win totals are not quite as high as some others in his era is that his manager for the entire 1950s, Casey Stengel, often saved Ford for special matchups, and did not pitch him every fourth day, which was the custom at the time. There were occasions when Ford pitched just once a week.

The numbers prove this. From 1953-60, when Whitey was arguably in his peak pitching years, ages 24-31, he averaged 28 starts under Stengel. From 1961-65, and ages 32-36, under new skipper Ralph Houk, and who famously told Whitey, “You’re my starter every fourth day,” Ford averaged 37 starts.

Let’s see, with maybe nine or ten extra starts those years, for a guy who likely would have won six or seven of them each year, okay, pessimistically even five or six, you’re looking at another 50 wins or so for the statboard.

And to this day, there are those who believe Stengel cost Ford, and his Yankees, another ring, in 1960.

Stengel held Ford back from pitching Game 1 in the 1960 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates. For whatever reason, he wanted him to start the first game in Yankee Stadium, Game 3. What? For better fan support? Who knows?

Ford pitched Games 3 and 6 and shutout the Buccos each time on his way to beating Babe Ruth’s World Series record of consecutive scoreless innings. Had he pitched Games 1, 4 and 7, a common practice with your Ace that still sometimes occurs, there might have been three shutouts on the resume and another big trophy in the Bronx.

And perhaps Bill Mazeroski is still waiting for his call from the Hall of Fame. Great player, great person, but it was his walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth in Game 7 that won it all for the Pirates, and likely punched his ticket for the Hall of Fame.

While Ford broke in enjoying the talents of the great Joe DiMaggio patrolling centerfield for the Yankees in 1950, but when he got out of the Army, there was a new centerfielder ensconced in the outer gardens of the big Bronx ballyard. Perhaps you’ve heard of him…Mickey Mantle.

Ford and Mantle. Mantle and Ford. The Country Boy and the City Slicker. They became fast friends and running partners, what’s now known as wingmen. They were Hope and Crosby. Martin and Lewis. Baseball’s Rat Pack along with their cohorts that often included Yogi Berra, Hank Bauer, and Billy Martin. They sometimes turned New York City into their personal playground.

There are stories, many of them, the most famous of which was a legendary fight one night at the Copacabana nightclub in 1957. Ford, Mantle, Martin, Berra, and Bauer were out celebrating Martin’s 29th birthday and enjoying a Sammy Davis, Jr. performance when other patrons were heckling the singing and dancing legend – some say with racist taunts, so the ballplayers backed Davis and punches were thrown.

Details have always remained sketchy, all these years later, there are several versions, some say that it was Bauer who started the fight, but one result was seeing Martin get traded. But that’s a tale for another day.

There are many memorable Mantle and Ford stories. Especially on-the-field exploits. There was a game when Whitey allowed Mickey to call his pitches, from centerfield! Like a Lucy episode where one says you-can’t-do-what-I-do, Whitey would casually turn to see Mantle before each pitch for some sort of secret sign, and obviously, the catcher was in on it too, and that’s what was called.

Then there was the All-Star game in 1961 where Whitey had to resort to using a “special” pitch to win a golf game bet.

Whitey and Mickey had played golf the day before the ’61 game in San Francisco’s Candelstick Park at a club where the Giants’ owner, Horace Stoneham, was a member, and they were told to just sign his name for whatever they wanted. They rang up a $200 tab, which was quite a sum in those days. Not now, of course, but back in the day, whew!

Instead of paying up, Stoneham issued Ford a double-or-nothing challenge. If he could strike out Willie Mays in the All-Star Game, they owed nothing, but if the Say Hey Kid got a hit, they owed $400.

In the book, “Voices of Cooperstown,” by Anthony Connor (find it, you’ll love it), Ford detailed the story.

“Mays was like 9 for 12 off me lifetime, and (Mantle) didn’t have any reason to think I was going to start getting Willie out, especially in his own ballpark, but I talked him into (accepting the bet).”

Mays came up to bat in the first inning, and of course, Ford was the starter in the year he went 25-4 and won his Cy Young.

“I got two strikes on him somehow, and now the money’s on the line because I might not get to throw to him again, so I did the only smart thing possible under the circumstances. I loaded up the ball real good and threw Willie the biggest spitball you ever saw.”

Strike Three!

“To this day, people are probably still wondering why Mickey came running in fr

jumping up in the air like we’d just won the World Series, and here it was only the end of the first inning in the All-Star Game.”

Mantle, who passed away in 1995 (can you believe it’s been 25 years?), often said about the buddy he called Slick. “I don’t care what the situation was, how high the stakes were – the bases could be loaded and the pennant riding on every pitch, it never bothered Whitey. He pitched his game, cool, crafty, nerves of steel.”

Baseball Heaven has been adding to its Hall of Fame pitching rotation far too often of late, with the deaths of greats Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson in the last month, plus the passings of Hall of Fame outfielders Al Kaline and Lou Brock.

The loss of Whitey Ford adds to the misery that has been 2020.

Whitey was fairly durable, but after the 1964 season, he underwent surgery on his left arm to repair a clogged artery. One weird byproduct of the surgery was that his arm lost its sweat glands.

He continued to endure arm problems off and on, and decided to retire during the 1967 season.

That made him eligible for the Hall of Fame in 1973, but that was part of the era when writers hated voting in players, regardless of their overwhelming accomplishments, on their first ballot, a practice which continued for decades, although of late the “tradition” is no longer as prevalent.

Instead, he joined the immortals of Cooperstown alongside Mantle in 1974, the year the Yankees also retired his number 16.

Ford first wore No. 19 as a rookie in 1950, but after his Army stint, he was switched to 16 in ’53.

In his autobiography, Ford of course qualified his Hall of Fame election as the highlight of his career.

“It was never anything I imagined was possible or anything I dared dream about when I was a kid growing up on the sidewalks of New York. I never really thought I would make it because I was too small.”

Small in stature, but a giant on the mound. That was Whitey Ford.

This fan once wrote that New York needs to honor one of its own native sons in a bigger way. Oh sure, there’s a ballfield named in Whitey’s honor in Astoria (on 26th Ave., in what’s known as Hallet’s Point), one that hosted a charity softball Home Run Derby in 2019, with plans for enlargements and new facilities in the future. But here was a true New Yorker who played his entire career in New York, and chose to live in retirement just over the city’s borders in Lake Success.

The suggestion was made before and we’ll repeat it again now. Hey, Mayor de Blasio, how about renaming Broadway in Astoria as Whitey Ford Blvd? It could have been done, should have been done, while Whitey was alive to appreciate it, but now, in the wake of his passing, let’s start another campaign to honor this great New Yorker.

Rest in peace, Chairman.

Photo: Jeff Zelevansky/Icon Sportswire